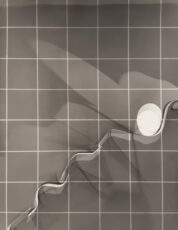

György Kepes (1906-2001)

Hand, Glass prisms (photogram)

Gelatin silver print

c. 1939

10 x 8 inches

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

György Kepes (1906–2001) was a Hungarian-born painter, designer, educator and art theorist. After emigrating to the U.S. in 1937, he taught design at the New Bauhaus (later the School of Design, then Institute of Design, then Illinois Institute of Design or IIT) in Chicago. In 1967, he founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) where he taught until his retirement in 1974. György Kepes had become acquainted with the theories of the Bauhaus and Constructivist movements as well as Dadaist expressions while moving in progressive circles in Budapest. He was apparently very impressed with the Dada photomontages of Hannah H ch and Raoul Hausmann. During the late 1920s and early 1930s he changed from photography and photocollage to making films. In the meantime Kepes had become familiar with the work of L szl Moholy-Nagy and collaborated with him in Berlin and London between 1930-1937. During his stay in London he also made the acquaintance of a science writer, J.J. Crowther, and it was through him that Kepes met some of England’s leading scientists – Joseph Needham, J.D. Bernal, and C.H. Waddington. When Moholy-Nagy invited him to Chicago in 1937 to head the Light and Color Department of the Institute of Design (also called the New Bauhaus) in order to “form a nucleus for an independent reliable educational center where art, science, technology will be united into a creative program,” Kepes accepted. There he developed light and color workshops in which various forms and techniques were researched on their visual and psychological impact. However, in 1945 he was invited to introduce a series of visual design courses in the School of Architecture and Planning, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge (MIT), something new at the time, and was subsequently offered the position of Professor of Visual Design and started the Center for Advanced Visual Culture (CAVS). His association with MIT would prove to be a long and fruitful one. During the following decades Gy rgy Kepes put his ideas on paper in a number of books which became widely publicized and gave him wide recognition as educator and theorist.

Simulated effects of a proposed mile-long programmed luminous wall, suggested for the Boston Harbor Bicentennial, 1964-65. The Language of Vision (1944) was his first attempt to connect the different languages of the different disciplines of knowledge, taking visual communication as a starting point. In particular the idioms of contemporary media like photography, motion pictures and television functioned in his eyes as a universal language that could be understood internationally. Coming from the Bauhaus and Constructivism, György Kepes was of course highly interested in an integration of the visual arts with the visual idioms of the daily environment, including design and architecture. He was able to develop this ideal vision through the interdisciplinary research groups which germinated at MIT around that time. This development was partly accelerated because of the school’s involvement in war research as a consequence of the United States’ activities in World War II. In 1942, a secret research group came together under the title Radar Laboratory. It was their task to develop a new electromagnetic radar system or anti-ballistic missile system, called Radio Detecting and Ranging. Rad Lab’s success was succeeded by the first interdisciplinary (a new term) laboratory at MIT: the Research Laboratory of Electronics in 1952. Its director was Jerome Wiesner, and one of the participants was Norbert Wiener, who was making a name in the science of cybernetics at that time. The interdisciplinary nature of these projects triggered Kepes’s interest to research possible relationships between art and science. While there was a growing exchange of ideas amongst a number of science departments, he noticed very little discourse between the humanities and science faculties. But even if many people thought that art and science were unmixable entities, Kepes was convinced that there existed a symbiotic relationship between the two, which would only grow stronger when nourished by each other. For him, technological progress was not in itself negative, but he warned against an uncontrolled utilization of it. Kepes: “The obvious world that we know on gross levels of sight, sound taste and touch, can be connected with the subtle world revealed by our scientific instruments and devices. Seen together, aerial maps of river estuaries and road systems, feathers, fern leaves, branching blood vessels, nerve ganglia, electron micrographs of crystals andthe tree-like patterns of electrical discharge-figures are connected, although they are vastly different in place, origin and scale … Their similarity of form is by no means accidental. As patterns of energy-gathering and energy-distribution, they are similar graphs generated by similar processes.” When Kepes tried to give an account of the different functions of the visual arts and the sciences, and what might connect them, he kept returning to the idea that nature served as a common base, as a common language for both. Being both ordering devices in that they try to impose a structure upon the human experience, art and science could have a complementary function in restoring the balance in today’s society, which he felt had been lost. What connected them further, argued Kepes, was that both art and science were “image-making devices” which needed to visualize experiences. For György Kepes it was no accident that there was such a remarkable similarity between certain paintings and photographs and the images that had become visible through new optical technologies such as infrared and ultraviolet rays, microscopic and telescopic photography, X-rays and other radiation techniques. Both were looking for laws, such as pattern, structure, harmony, order or even disorder in natural and other phenomena. These technologies offered a completely new picture of nature’s order, which had hitherto been invisible to the human eye, giving new sensory experiences and expanding the range of perception. In order to make his findings known to the public, he organized an exhibition titled The New Landscape (1951), in which he presented the visual analogues between recent scientific visualizations of research models and the visual arts. Computer images, serial and other photographs of the “micro-world” and “macro-world” made by scientists, were presented next to artist’s images, showing analogous forms and patterns. A few years later he published The New Landscape in Art and Science (1956), in which he “attempted to present in pictures the new visual world revealed by science and technology, things that were previously too big or too small, too opaque or too fast for the unaided eye to see.”

György Kepes gradually moved beyond a comparison of visual analogues, on to another level of relationships between art and science. He felt that the scientific concerns with the invisible micro-world in terms of energy or dynamic organization instead of measurable, and tangible objects could be compared to the changes in the visual arts. The fact that sculptors had turned to new ‘immaterial’ technologies of light, video or laser was representative of this new way of thinking for him. Kepes was convinced that if artists and scientists were to work in a closer communion, it might be possible that artists would work out new visual images that could inspire scientists in their search for new visual models. After the publication of The New Landscape in Art and Science, György Kepes’s contributions to books and catalogues almost always revolved around a serious concern about the earth and the environment, emphasizing the thoughtless manner in which man-kind treats nature’s treasures. His arguments grew stronger in the early seventies when the ecological movement was rapidly gaining a large following and environmental concerns were vehemently and emotionally discussed in books like Charles Reich’s The Greening of America or Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. Kepes: “Our cities are our collective selfportraits, images of hollowness and chaos. And if not properly guided our immensely potent technology may carry within itself curses of even more awesome proportions. The yet not understood uncontrolled dynamics of scientific technology could do more than poison

our earth; it is capable of wreaking havoc on man’s genetic nature.” (1972) It is here that Kepes found a social as well as educational role for the artist. Only an artist who was knowledgeable about the developments in science and understood the implications of new technologies could influence the expected environmental problems. For Kepes, this meant a new civic art (his term), based on interdisciplinary collaboration. One way to expand the vision of art was to create an exchange and communication for art with other disciplines, in particular the sciences. “In becoming a collaborative enterprise in which artists, scientists, urban planners and engineers are interdependent, art clearly enters a new phase of orientation in which its prime goal is the revitalization of the entire human environment; a greatly-to-be-wished-for climax to the rebuilding of our present urban world.” (1971: 72)

Books

The Language of Vision: Painting, Photography, Advertising-Design, intro. Siegfried Giedion and Samuel Ichiye

Hayakawa, Chicago: Paul Theobald, 1944; rev.ed., Chicago: Paul Theobald, 1964.

Sprache des Sehens, trans. Renate Pfriem und Almut v. Wulffen, Mainz and Berlin: Kupferberg, 1944, 200 pp.

(German)

El Lenguaje de la visi n, trans. Enrique L. Revol, Buenos Aires: Infinito, 1969, 302 pp. (Spanish)

Il linguaggio della visione, trans. Franca Rossi Chiaia, Bari: Dedalo, 1971, 253 pp. (Italian)

Shikaku gengo: kaiga shashin kōkoku dezain e no tebiki [ : 絵画・写真・広告デザインへの手引],

Tokyo: Gurafikku Sha, 1973, 201 pp. (Japanese)

A l t s nyelve, trans. Katalin Horv th, Budapest: Gondolat, 1979, 253 pp. (Hungarian)

Kepes, et al., Graphic Forms: the Arts as Related to the Book, Harvard University Press, 1949. Based on a series

of four public meetings held on 17-18 January 1949 at the Fogg Museum of Art in Cambridge, 128 pp.

editor, The New Landscape in Art and Science, foreword John E. Burchard, Chicago: Paul Theobold, 1956, 384

pp; 4th ed., 1967. Contributions by sculptor Naum Gabo, physicist Bruno Rossi, art-historian Siegfried Giedion,

architect Richard Neutra, psychologist Heinz Werner, cybernetician Norbert Wiener, and writer Charles Morris.

Review: Alford (1958).

Zōkei to kagaku no atarashii fūkei [造形と科学の新しい 景], Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppansha, 1966. (Japanese)

The Visual Arts Today, Wesleyan University Press, 1960.

La situaci n actual de las artes visuales, Buenos Aires: Tres, 1963, 124 pp. (Spanish)

editor, Education of Vision, New York: George Braziller, 1965.

Education de la vision, trans. Dani le Panchout, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1967, xiv+213 pp. (French)

Visuelle Erziehung, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1967, xiv+233 pp. (German)

La educaci n visual, M xico: Novaro, 1968, vii+233 pp. (Spanish)

editor, Structure in Art and in Science, New York: George Braziller, 1965.

La structure dans les arts et dans les lettres, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1967, xv+189 pp. (French)

Struktur in Kunst und Wissenschaft, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1967, xv+189 pp. (German)

La estructura en el arte y en la ciencia, trans. Agust Bartra, M xico, D.F.: Novaro, 1970, vii+189 pp. (Spanish)

editor, The Nature and Art of Motion, New York: George Braziller, 1965, 195 pp. Review: Steele (1966).

Nature et art du mouvement, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1968, 195 pp. (French)

Wesen und Kunst der Bewegung, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1969, xviii+195 pp. (German)

El movimiento: su esencia y su est tica, trans. Agust Bartra and Sergio Madero, M xico, D.F.: Novaro, 1970, xi

+195 pp. (Spanish)

editor, Module, Proportion, Symmetry, Rhythm, New York: George Braziller, 1966.

Module, proportion, sym trie, rythme, trans. Dani le Panchout, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1968, 233 pp.

(French)

Modul, Proportion, Symmetrie, Rhytmus, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1969, 233 pp. (German)

editor, The Man-Made Object, New York: George Braziller, 1966, 230 pp.

L’Objet cr par l’homme, trans. Dani le Panchout, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1968, 230 pp. (French)

Der Mensch und seine Dinge, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1972, 192 pp. (German)

editor, Sign Image Symbol, New York: George Braziller, 1966.

Signe, image, symbole, trans. Dani le Panchout, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1968, 235 pp. (French)

Zeichen, Bild, Symbol, Brussels: La Connaissance, 1972, 174 pp. (German)

editor, Arts of the Environment, New York: G. Braziller, 1972.

El arte del ambiente, trans. Nely Coarasa, Buenos Aires: Victor Ler , 1978, 193 pp. (Spanish)

El arte y la tecnolog a: hacia la reconstrucci n del medio ambiente urbano, Bogot : Universidad de los Andes,

1973, 51 pp. (Spanish)

L’arte visuale oggi: antologia di scritti, ed. & trans. Branka Jankovic Russo, intro. Gianni Pirrone, Palermo: S.F.

Flaccovio, 1977, 176 pp. (Italian)

Explorations: Toward Civic Art, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1970, 8 pp. Held on 4 Apr-10 May

1970.

The MIT Years 1945-1977, MIT Press, 1978, 104 pp. Exhibition held at Hayden Gallery, 28 April – 9 June 1978.

The Pleasure of Light: Gy rgy Kepes and Frank J. Malina at the Intersection of Science and Art, 2011, 189 pp.

(English)/(Polish) Exhibition held at the National Museum in Gdansk; curated by Nina Czegledy and Rona

Kopeczky.

Articles

“Function in Modern Design”, in Kepes, et al., Graphic Forms: the Arts as Related to the Book, Harvard

University Press, 1949; repr. in Looking Closer 3, eds. M. Bierut, J. Helfand, S. Heller and R. Poynor, New York:

Allworth Press, 1999, pp 98-105.

“Notes on Expression and Communication in the Cityscape”, Daedalus 90:1 (Winter 1961), pp 147-165.

“Kent l eginde Disavurum ve Iletisim zerine Notlar”, trans. Bahar cal Düzg ren, Cogito 8: “Kent ve

Kültürü”, 2014, pp 177-192. (Turkish)

“The Visual Arts and the Sciences: A Proposal for Collaboration”, Daedalus 94:1 (Winter 1965), pp 117-134. [1]

“Light and Design”, Design Quarterly 68 (1967), pp 1-2 & 4-32.

“The Lost Pageantry of Nature”, Arts Canada (Dec 1968), pp 33-39.

“L szl Moholy-Nagy: The Bauhaus Tradition”, Print 23 (Jan-Feb 1969), pp 35-39

“Toward Civic Art”, Leonardo 4:1 (Winter 1971), Pergamon Press, pp 69-73; repr. in Arts in Society 9(1):

“Environment and Culture”, University of Wisconsin, 1972, pp 83-94. Based on a text published in connection

with the exhibition ‘Explorations’ held at the National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D.C., from 4 April-10 May 1970.

“Art and Ecological Consciousness”, in Arts of the Environment, ed. Kepes, New York: G. Braziller, 1972, pp

1-12.

“The Artist’s Role in Environmental Self-regulation”, in Arts of the Environment, ed. Kepes, New York: G.

Braziller, 1972, pp 167-191.

Literature

Jasia Reichardt, “Art at Large”, New Scientist, 1 Jun 1972, p 525.

Judith Wechsler, “Gyorgy Kepes”, in The MIT Years 1945-1977, MIT Press, 1978, pp 7-19.

Jonathan Benthall, “Kepes’ Center at MIT”, Art International 19:1 (Jan 1975), pp 28-31+49.

Marga Bijvoet, “Interdisciplinary Collaborations: Ideas”, ch. 1 in Bijvoet, Art as Inquiry: Toward New

Collaborations Between Art, Science, and Technology, Peter Lang, 1997.

“Interdisziplin res Gemeinschaftswerk: Pl ne”, ch. 1 in Bijvoet, Kunst-Forschung, n.d. (German)

Anne Collins Goodyear, “György Kepes, Billy Kluver, and American Art of the 1960s: Defining Attitudes Toward

Science and Technology”, Science in Context 17:4 (2004), pp 611-635.

The Kepes Journal, since 2004. (Spanish)/(English)

Leigh Anne Roach, A Positive, Popular Art: Sources, Structure, and Impact of Gyorgy Kepes’ ‘Language of

Vision’, Florida State University, 2010, 154 pp. Dissertation.

Anna Vallye, Design and the Politics of Knowledge in America, 1937-1967: Walter Gropius, Gyorgy Kepes,

Columbia University, 2011. Dissertation.

Orit Halpern, “Visualizing: Design, Communicative Objectivity, and the Interface”, ch. 2 in Halpern, Beautiful

Data. A History of Vision and Reason since 1945, Duke University Press, 2014, pp 79-144

John R. Blakinger, Gy rgy Kepes: Undreaming the Bauhaus, MIT Press, 2019, 504 pp. [2